Why Injection Time Measurement Matters—and How We’re Improving It

A sensor-based approach to injection time measurement in medical device usability studies

by Cameron Murr

In recent years, there has been a noticeable trend of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requesting more and more data from human factors (HF) professionals in order to satisfy usability requirements. And here at Design Science, we are always exploring ways to gather more comprehensive data to provide manufacturers for use in their submissions. We frequently leverage advanced data collection tools that allow for a more thorough understanding of user action and intention. Our eye tracking system, for example, assists in the development of instructions for use (IFU) by giving our researchers information on what a user sees and, more importantly, what they do not see. And now, with the FDA seeking more detailed and accurate information from manufacturers, we have identified a gap in the current data collection standard for autoinjector (AI) studies. The current state of the art for measuring user injection times is for researchers to use a stopwatch or video frame review to manually time the injection. For cases in which the user follows the appropriate injection steps and abides by the hold time stated in the IFU, this may be sufficient as they will have delivered a full dose of medication. However, for situations in which a user does not deliver a full dose of medication, it is crucial to know precisely how long they held for. Having accurate injection times allows for the possibility of comparing against manufacturer bench testing of their device. For cases in which a full dose was delivered despite the user not holding for the instructed time, this data can be used to support the case of residual risk being acceptable. And in cases where a full dose was not delivered, it can be determined what percentage of the dose was delivered in order to accurately assess the severity of such a use error. In response, Design Science has developed a sensor system to automatically measure a user’s injection time with an AI.

There are a variety of factors that limit the accuracy and precision of manual timing. First off, human reaction time has been shown to introduce a timing error with a standard deviation of 0.10 seconds for events involving both a manual start and manual stop (Faux, 2019). Further studies have shown that human timers with less experience tend to have greater timing deviations and variability in their measurements (Radner, 2016). Additionally, due to the needle guard blocking the needle from view, the visual stimuli for when an injection begins and ends is unclear. These factors introduce error in recording injection times during usability studies due to the limitations of human reaction time, variability due to different researchers, and uncertainty over when an injection begins and ends.

Our system addresses these issues by using sensors to detect when the needle from an AI is actively piercing the injection site along with audible feedback (“clicks”) from the device. And in the spirit of maintaining realism during usability studies, the sensors are integrated into the injection pads that we use during our test sessions, allowing the devices to be both mechanically and visually unaltered. This has allowed for seamless integration into our HF testing and in doing so, we are able to collect better data that can be leveraged in residual risk discussions without sacrificing the authenticity of the simulated environment.

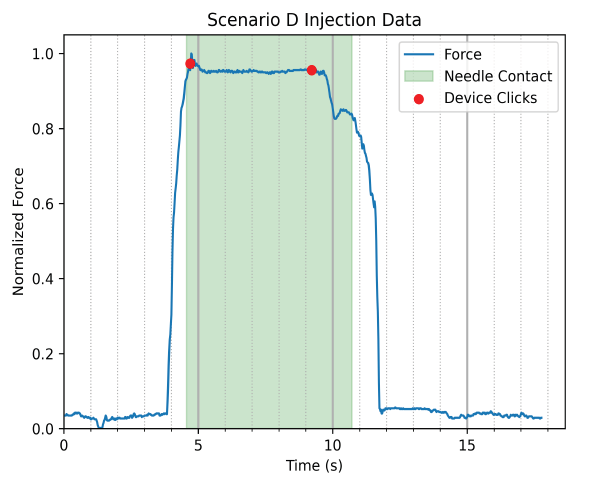

This system collects data on when the needle is penetrating the injection pad, when the autoinjector emits clicks, and measures the force applied to the injection pad. These metrics allow for analysis of participant action throughout the entire injection. The outputs of the system include the entire needle penetration time, the click-to-click time, and the time between the second click and the exit of the needle from the injection pad. Additionally, plots are generated to better visualize the injection, as illustrated by the figure below,

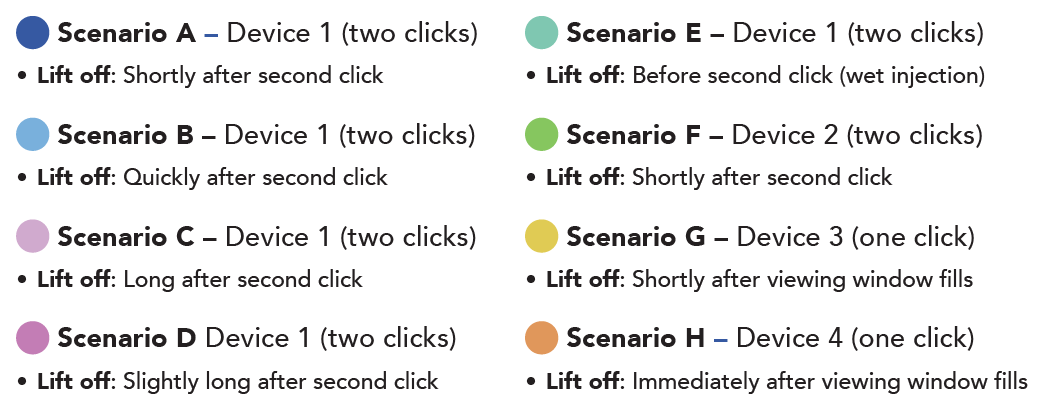

We wanted to get a better understanding of how HF researchers matched up against our system. To do so, we designed a study to compare manual timing to the automatically recorded times measured by our system. Sixteen researchers performed timing measures on eight commonly observed scenarios reflective of commonly observed participant actions during AI injection usability studies.

The results showed that there was a statistically significant difference between the actual times the injections were being delivered and the average manual times reported by HF researchers. Additionally, the accuracy of hand timing was seen to be subjective to the actions taken by the user. For example, when the user slowly removes the device from the injection site, the manual times become noticeably longer than the actual injection time. This is likely due to the fact that the needle will exit the injection site before the needle guard is fully locked-out while an observers only visual stimulus that the injection has ended is the needle guard fully locking-out and the AI being removed from the injection site. Our primary takeaway from this study is that while manual timing of injections by experienced HF researchers is reasonably accurate, manufacturers have the opportunity to be more precise in determining if a use event may result in harm and be more granular in assessing the severity of incomplete injections. Consider an autoinjector known to take 4.5 ± 0.3 seconds to deliver a full dose and its IFU instructs users to hold for 5 seconds. In a study, participant 1 lifts off after 4.25 seconds and participant 2 lifts off after 4.85 seconds. For participant 1, it can be calculated that they delivered approximately 90% of a full dose, resulting in a severity of harm of 2 rather than the severity of harm of 4 for receiving less than 25% of a full dose. For participant 2, the residual risk discussion can now focus on the fact that despite lifting off early, the participant still delivered a full dose and as a result, there is no potential for harm.

With this system, we have been able to provide clients with exact injection times that they have then used to determine the percentage of dose delivered for each injection, providing deeper insight into the severity of harm associated with each individual underdose, previously not possible with manual timing. This has been especially helpful in situations where the user lifts off slightly during the injection, making it difficult to visually determine if the needle has exited the injection site or not, and when users lift off immediately after the second click as the full dose may not have actually been delivered.

Additionally, this system can be used to better understand user intention versus action. AI IFUs typically provide instruction on how long a user should depress the AI in order to deliver a full dose. By having accurate injection times, researchers have the ability to better assess a participant’s intentions in relation to their actions and their adherence to the IFU. By then discussing possible discrepancies between action and intention with participants, researchers can then determine the optimal hold time to state in the IFU for ensuring that users do not lift off too soon during the injection. For example, if an autoinjector is known to take, on average, 4.5 seconds to deliver an injection with an IFU instructing users to hold for 5 seconds, and participants were seen to only hold for an average of 4.2 seconds, then a possible update to the IFU could be to instruct users to hold for 6 seconds to account for a tendency to count too quickly.

Another advantage that we have seen using this system is in the automation of our data collection process. With manual timing, we review session recordings to confirm that the documented injection times are reasonably accurate and the process of locating when injections occur during each session is time-consuming. With our system, the injection time data is generated in a ready-to-use table along with plots for use in our reports.

In summary, manual timing of injections will continue to be a serviceable option for HF testing, but we are moving towards more advanced tools to gather higher-quality data to support better product design while also increasing efficiency in our data collection methods. Here at Design Science we are always looking for ways to improve usability research in an effort to improve outcomes in the healthcare space. If you are interested in getting the most actionable data out of your HF efforts, contact Design Science today to learn more.

References

Faux, D. A., & Godolphin, J. (2019). Manual timing in physics experiments: Error and uncertainty. American Journal of Physics, 87(2), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.5085437

Radner, W., Diendorfer, G., Kainrath, B., & Kollmitzer, C. (2016). The accuracy of reading speed measurement by stopwatch versus measurement with an automated computer program (rad‐rd©). Acta Ophthalmologica, 95(2), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13201

Share this entry